A title

Image Box text

About John

John lives with his wife and two kids in Solana Beach, California. They spend most of their free time fishing, surfing, beachcombing, and the like. John was immediately drawn to nature and fish printing and has found endless inspiration in the activities he does and the work of other nature print artists. John and his son regularly fish the San Diego waters from their jetski and John’s prints are mostly of fish they catch locally. John is constantly experimenting with different inks and materials and always on the lookout for new subject in nature to incorporate into his work.

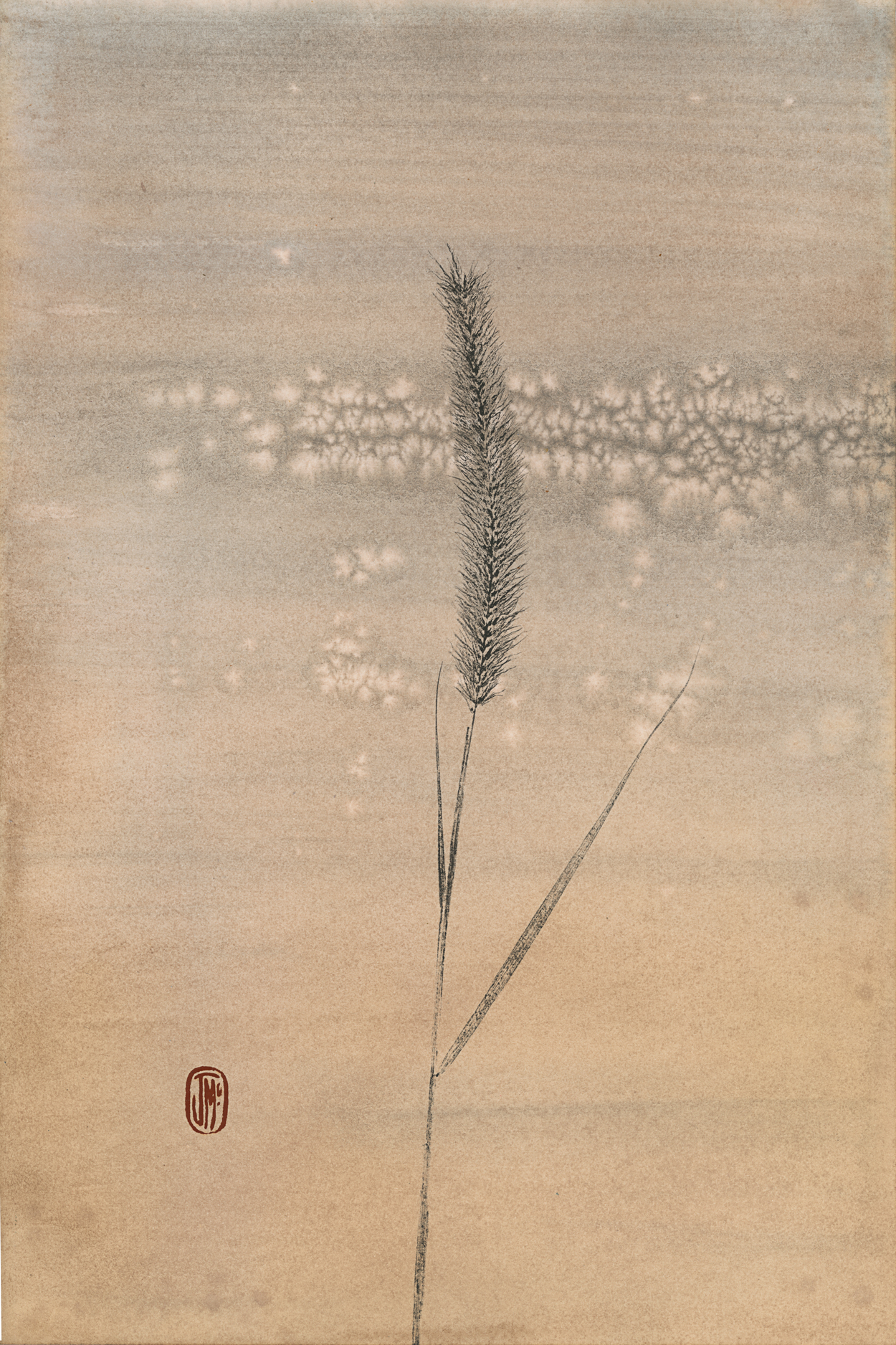

Nature Printing

“Nature printing” is a broad category of art and encompasses printing of everything from plants and woodcuts to fish and insects. Nature printers use all kinds of inks, paints, and pigments and print on a variety of papers and other surfaces.

But nature printing isn’t a new method. For many thousands of years people have been using various pigments to print images of plants, animals, and even themselves. For instance, hand prints in Cueva de las Manos in Argentina date back to approximately 7,000 B.C. And long before photography was invented, chemists and botanists used plant prints to identify and catalogue different species. Ben Franklin even utilized molds made from leaf prints to create currency that—because of the intricacy of the leaf—was less susceptible to counterfeiting than other designs.

The detail of leaf prints that Ben Franklin found useful to guard against counterfeiters, is the same attribute that gives nature printing such authentic beauty. There’s something about printing (as opposed to a painting or photograph) that gives the work a uniquely eye-catching and dramatic quality. Through the use of a various materials, techniques, and compositions, the printer can highlight and showcase the inherent, subtle beauty of the natural world, which is the subject of this type of art.

A title

Image Box text

A title

Image Box text

Nature Printing Process with Plants

Nature printers use lots of different methods and materials to create their work. But nature printing typically involves applying ink or another pigment to the subject (a leaf, for instance) and then applying the inked subject to paper or some other surface. When the subject is removed from the printing surface, an image of the subject is left behind.

Artists use various tools (like brushes and brayers) to apply pigments and lots of different types of papers and surfaces to print onto. John’s process typically involves printing in oil-based ink onto paper that he hand dyes with inks ahead of time. He generally dries and presses the plants he prints (which can take several days or more) prior to printing. He then uses a brayer to apply the ink to the dried plant and either presses the paper on the plant or presses the plant on the paper using another sheet of paper on top (sandwiching the plant between the two sheets).

Gyotaku Process (Fish Printing)

Printing the fish. Gyotaku (fish printing) is the process of creating an ink print from a real fish. The basic process of “direct” fish printing simple: the artist brushes ink on the fish and then presses a piece of paper over the top of the inked fish. When the artist peels the paper back, an ink print of the fish comes off on the paper. (There’s also an “indirect” method that’s a bit different.)

Materials. Gyotaku artists traditionally used an ink made from pine soot and water called “sumi” ink and a thin, strong paper made from mulberry (“kozo”) bark called “washi.” Though contemporary gyotaku artists use different papers and inks for their work, John generally uses the traditional materials—sumi ink and washi—to create his prints.

Eating the fish. Sumi ink is non-toxic, so it can simply be removed with water after printing. Once the ink is removed, the fish can be cleaned and eaten.

Final touches. The details of the fish eye doesn’t come out in the print. So most fish printers will paint in the eye and might make a few other finishing touches with a brush.

Flattening. The paper used in printing ends up wrinkled because of the contours of the fish. Some prefer to leave the wrinkles, but you can also remove the wrinkles (“flatten” the print) through a process called “wet mounting.” Wet mounting basically involves laying the print face down on a flat surface, brushing the back with a paste made from water and wheat starch, and pressing another sheet of paper on top. When you peel the two sheets off the flat surface, they will be stuck together and the wrinkles will be gone (assuming all went well). You then stick the print face up to another flat surface and let it dry for a day or so.

History of Gyotaku

It’s believed that fish printing (called “gyotaku” in Japanese) originated in Japan in the 1800s or before. The oldest known fish print still in existence was commissioned by a samurai lord named Sakai around 1860. There are different stories about what fish printing was originally used for in Japan. One story is that Sakai, who enjoyed fishing, invented fish printing as a way to document his best catches, much like how a fisherman now days would take a photo. Another story is that fishermen, who couldn’t write, first used fish prints to advertise what they had for sale that day. But, whatever the original purpose, gyotaku evolved over time into an art form in its own right.

A title

Image Box text